Your Multimodal/Cinematic Journal

In the two previous pages:

What is Multimodal/Cinematic Journal?

What is Multimodal/Cinematic Communication?

you read extensively about what multimodality and cinematic expressions are and what important role they play in the Ripples@Work Startup Venture learning.

In this article, we talk about how to use your Multimodal/Cinematic Journal.

Like any other components in R@W, your M/C Journal is a part of a ‘dialogue’ between challenging positions. Your M/C Journal helps you to move beyond passive absorption of information gained by generating your research data through interactions with your surroundings and your teammates.

In M/C Journal, you continuously compare your attitudes, understanding, perception with those of what you see in the world and how your teammates understand them.

While there are many platforms on the educational market to fit your technological and aesthetic preferences, the one R@W strongly recommends you to begin with is Canva.

It is a very simple process to set up your account on Canva for free. Just follow the prompts on:

https://www.canva.com/education/

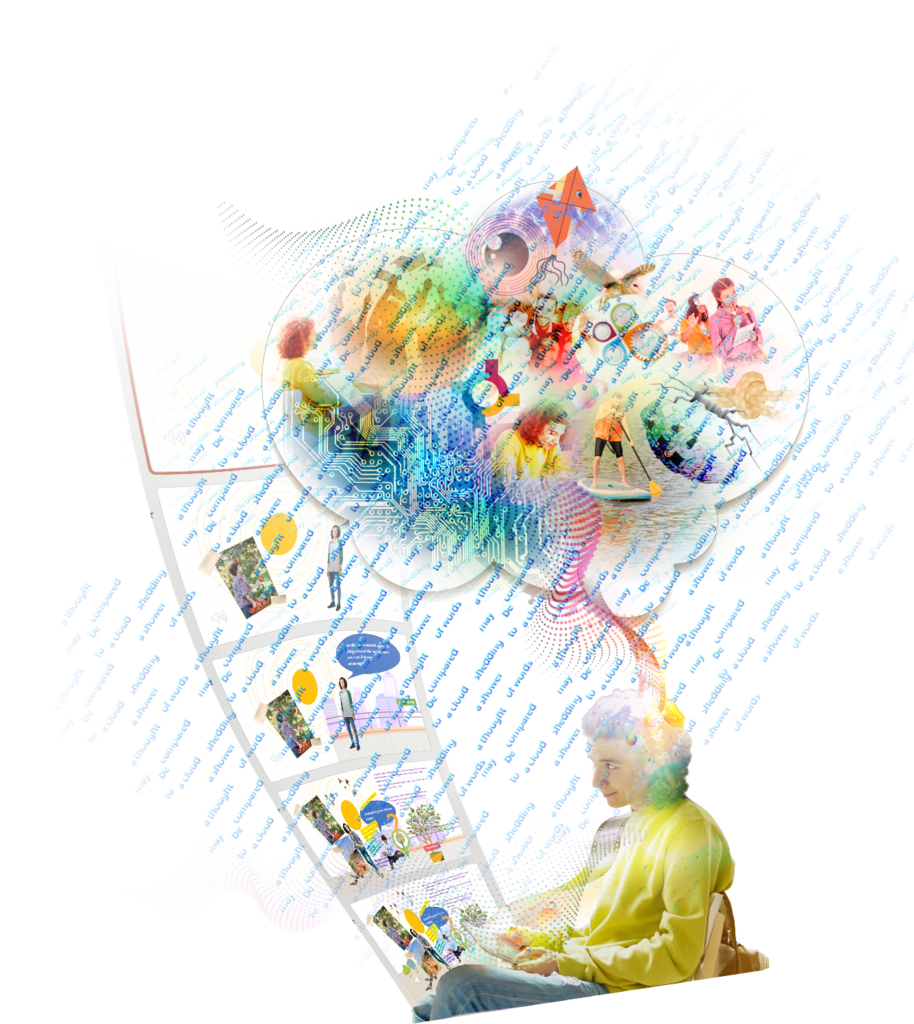

In Ripples@Work, we employ cinematic writing, which is carried out using multimodal forms of expression—writing with text, images, sounds and animations. As you generate data on a topic and become more comfortable with the use of multimodal elements, your writing turns into a medium for analysing the processes of the mind.

‘The shower of words,’[i] flashes of memories, traces of shapes, and tingles of sensations that we’re continuously experiencing through our mind-cinema, become the material for making meaning of your inner virtual world. The R@W goal is to engage you in a metacognitive activity —thinking about your own thinking.

These self-reflective or metacognitive activities involve creative representation of your mind-cinema using multimodal components—text, images, sounds and animations.

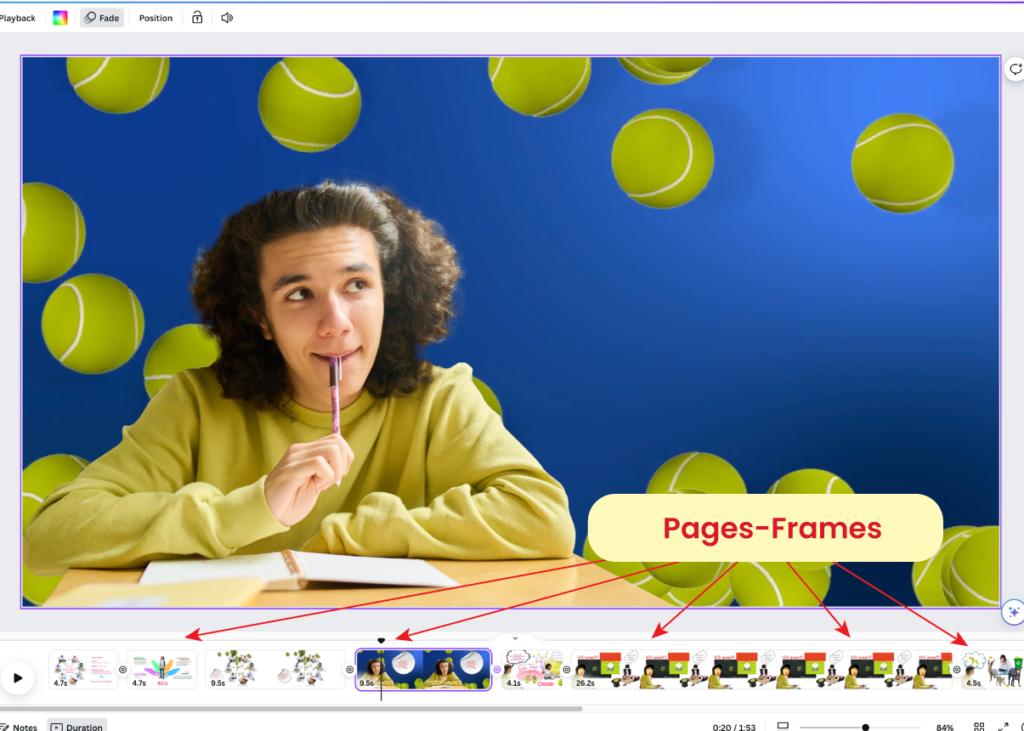

Consider a page of a cinematic journal (CJ) as one frame within a sequence of page-frames that constitute the learning project.

‘The contents of the frame and the way that they are organized’[ii] are termed in cinematography the mise-en-scène. The term refers to the elements of the scene, including the actors, as well as the style in which they combine to project a particular atmosphere in a cinematic story.

The idea of cinematic writing takes its roots from the origins of cinematic expression.

The word cinematography comes from two Greek roots: kinesis (the root of cinema), meaning movement, and grapho, which means to write or record. […] Writing with movement and light—it’s a great way to begin to think about the cinematographic content of motion pictures.[iii]

In this light, we see cinematic writing as writing with images, sounds and movement (animation or video). We adopt the concept of mise-en-scène to describe the way in which a learner consciously creates an atmosphere that is authentic to that individual.

German perceptual psychologist and film theorist Rudolf Arnheim once wrote: ‘The human mind is not easily accessible […] the person’s own mind, tends to shrink when it is watched.”[iv]

So, your task in producing a successful cinematic event—a story of your thinking about your thinking—is to create a sense of security and comfort for your own mind by using the components that you enjoy working with and that help you to establish a secure interplay between what is happening in your mind and what is projected through your cinematic writing.

Think about the screen of the digital device you’re working with as a portal that lets you move from the virtual world of your mind to the virtual digital world of the CJ.

That’s why we are talking about tinkering, something you do without much planning and evaluation before doing it. It is essential to trust yourself and be brave enough to respond to your impulses (if they are not hurting yourself or anyone else, of course ).

As the R@W metacognitive activity of cinematic writing is aimed at making sense of your inner mind-cinema, you should learn to ‘catch’ things from your mind and let them out—to be represented in your CJ.

Thoughts are triggered by our ‘desires and needs, our interests and emotions.’[v] In other words, our thoughts are the reflections of our unique experiences of being in the world. Through cinematic writing, we embody our thoughts and our feelings in visible or audible form.

For example, we can express feelings of anxiety by inserting the sound of the steps and ice cracking under the feet. Or by adding graphics of crows crying chaotically while flying across the page. In this way, we give an intangible feeling a ‘physical body’ by embodying it in a physical form, sound or movement.

The elements of cinematic writing—graphic design (GD) elements and generated multimodal assets—are discussed in the previous document.

They are the ‘what?’—GD elements, images, sounds, video and animation pieces, etc.

To use certain elements and tools cinematically, it’s important to know ‘why’—to comprehend the reason behind their use. It’s not about deciding whether or not to use them, but rather questioning why have you employed them.

And you have to experiment with ‘how?’—how to use the affordances of digital media to remix the elements, assets and existing knowledge into a meaningful interplay.

The term affordances[vi] was coined by American psychologist James J. Gibson. Gibson says that he made up the term to refer to what the environment offers to an individual organism.

When we talk about affordances in R@W, we refer to human—digital technology interactions. That is, what digital technology offers us and how you find your smart individual ways to take advantage of these affordances. Digital technology includes the World Wide Web, a virtual world of games and simulations, digital equipment, tools and software.

PowerPoint, despite being so widespread, has a range of affordances that are used rarely, poorly, or hardly at all. PowerPoint has become synonymous with boring slideshows that lack creativity, and as a result, for many people, the program has negative associations.

The learner may not know about the affordances of PowerPoint but discover them through the process of achieving their goals. And they may find ways to remix those affordances with the affordances of the internet and other digital tools to produce a meaningful outcome.

PAGES—FRAMES

Consider a page of a cinematic journal (CJ) as one frame within a sequence of page-frames that constitute the learning project.

MIND-CINEMA

‘The shower of words,’[i] flashes of memories, traces of shapes, and tingles of sensations that we’re continuously experiencing through our mind-cinema, become the material for making meaning of your inner virtual world. The R@W goal is to engage you in a metacognitive activity —thinking about your own thinking.

HUMAN MIND and TECHNOLOGY INTERACTIONS through DIGITAL MEDIA AFFORDANCES

Digital Media Affordances refer to the range of functionalities that a specific unit of digital media can offer

Cinematic Writing Components

So, to create a cinematic event—a story of your thinking—you’re working with the following cinematic aspects:

- avatar—your representation of yourself. The CJ is about you, your potential, your growing awareness, understanding traits in your behavior, and developing independent, but at the same time, collaborative approaches to fixing problems and solving dilemmas. You’re the main character of your cinematic story. To represent yourself, you can either take selfies or ask someone to take photos of yourself or create an avatar to represent yourself. With cinematic writing, you’re creating learning conditions for yourself to understand your interactions with the surrounding world.

- mind-cinema—the shower of words, flashes of memories, traces of shapes, and tingles of sensations that are continuously playing in your mind. This is what you are trying to represent, analyse, understand and, ultimately, improve.

- cinematic frames—CJ pages. This is where you create cinematic events.

- media assets—multimodal items self-generated or taken from digital media online stocks for the topic of the project and converted into a digital form. This is also existing knowledge— scientific facts, theories, algorithms, explanations of phenomena, and historical records that can be found on the internet or in printed material. This is what you use to contrast and compare your ideas and aspirations and to create cinematic events.

- GD elements. This is what you use to organize assets into meaningful accounts of your thinking.

- digital media affordances. This is what digital technology offers and you have your smart ‘youness’ in finding your own unique ways of using it.

Using these tools, you craft a cinematic event in which you are the protagonist.

Your CJ consists of a series of cinematic events telling the story of your self-regulatory processes and cognitive growth.

As you collect materials for your research, you generate the assets that are used in creating events: photos, video and audio recordings, screenshots, existing facts, etc. By themselves, they are just data. You create an event when you begin to bring them into an interplay with each other to reflect your mind-cinema, where you are an observer/creator as well as an actor.

If you insert a photo in the CJ frame just because you’ve taken it yourself and it is nice, then describe it and decorate it prettily, your activity could be counted as multimodal writing but not metacognitive or, as we refer to it in R@W, cinematic writing It may be a great activity but we are striving for metacognitive activities where your thinking is observed and conditions are created for your cognitive development.

In creating a cinematic event, progress is driven by continuous self-questioning. And the unique approach to this process is that you don’t restrict yourself by a linear order of actions. You can do something that feels right, and only then ask yourself, ‘Why did I do this?’ If your evaluation is positive, you build on it or make necessary adjustments. For example, your explanation may seem great, but the element or asset you’ve used needs to be replaced by something more relevant. Or maybe you realise that there is a better way of conveying your message.

Asking yourself questions may appear burdensome. But try to observe how your mind works—even though you don’t articulate questions when you do something, most of the time they cross your mind. The difference is that, usually, they flash through your mind so quickly that you don’t stop to ponder them.

Cinematic writing is about catching those disembodied flashes of mind-cinema, trying to decode their messages by representing them—giving them a look, a voice, or a movement. In other words, making sense of them by embodying them in something that is perceptible.

In doing this serious work, we use the technique of strategic tinkering, or we say, remixing.

Strategic tinkering is an intentional remixing of the elements, assets, existing knowledge and technological affordances by cinematic writing. Intentionality and remixing are the two concentric rings of strategic tinkering.

MULTIMODAL WRITING (writing with text, images, sounds, and animations)

+ METACOGNITIVE ACTIVITIES (thinking about your thinking)

= CINEMATIC WRITING

CINEMATIC WRITING EVENT — a multimodal story of your thinking in one frame.

EMBODIMENT — giving a thought a body; representing it with text, shape, form and/or sound, or movement.

STRATEGIC TINKERING — the intentional remixing of graphic design elements, media assets, existing knowledge, and technological affordances for the purpose of making meaning.

REFERENCES

[i] Vygotsky, Lev S. (1934). Thought and Language [Kindle version, 2012, loc 346]. In E. Hanfmann, G. Vakar & A. Kozulin (Eds). Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

[ii] Gibss, John (2012). Mise-en-scene: Film Style and Interpretation (Short Cuts) [Kindle version]. WallFlower Press.

[iii] Sikov, Ed (2010). Film Studies: An Introduction [Kindle version]. In Film and Culture Series, A. Orman & J. Belton (Eds). Columbia University Press.

[iv] Arnheim, Rudolf (2006). The Genesis of Painting: Picasso’s Guernica. California: The Regents of the University of California.

[v] Vygotsky, Lev S. (1934). Thought and Language [Kindle version, 2012, p. 267]. In E. Hanfmann, G. Vakar & A. Kozulin (Eds). Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

[vi] Gibson, J. J. (1979). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception: Classic Edition [Kindle version, 2015, p. 119]. Psychology Press. Taylor & Francis Group.