Cognitive Adaptation

Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive adaptation is the central psychological mechanism in the R@W learning process. It derives from a fusion of three other theoretical dimensions which we have looked at on the Theoretical Framework page, and completes the theoretical foundation of the model.

In Piaget’s theory of cognitive adaptation, individualization is promoted by placing an individual learner center stage in acquiring his or her knowledge. Each individual has characteristics that vary from those of others. Given positive conditions for their development, these individual variations are foundational for the development of the learner’s individual agency.

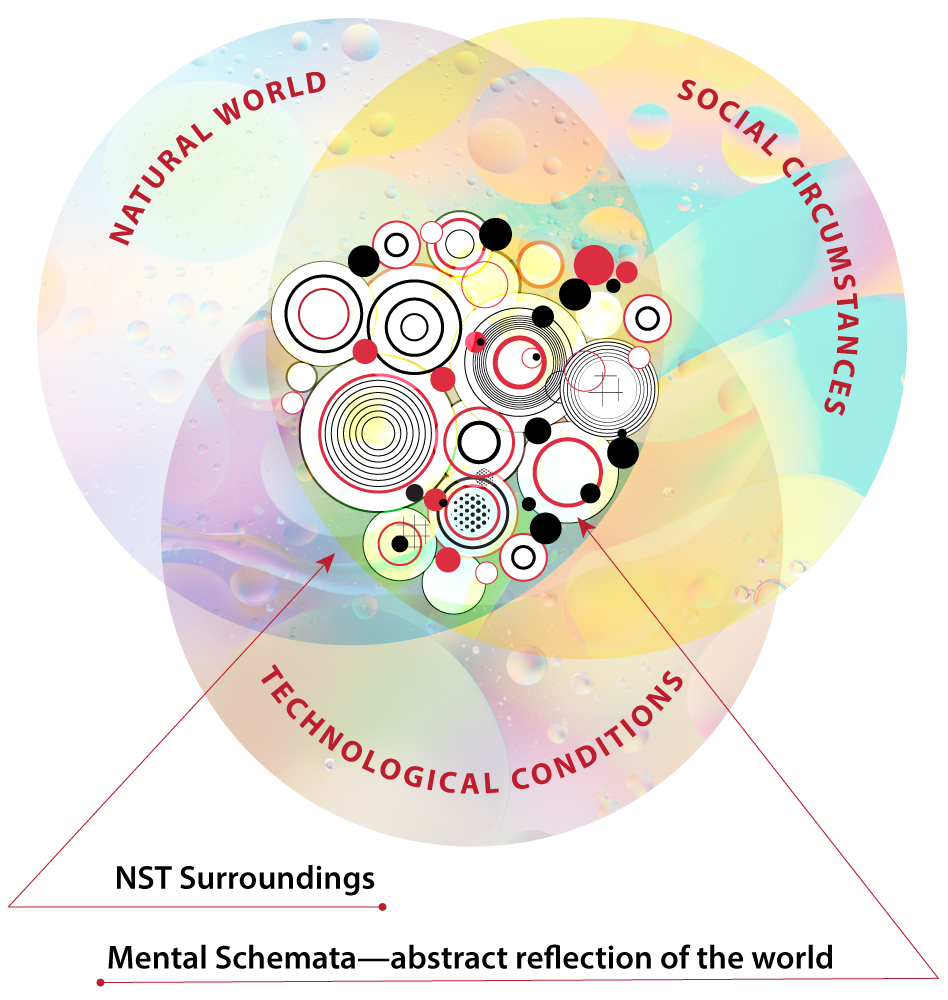

Systems thinking helps us to see an individual learner as a unique psychological system characterized by its own ‘jagged profile’. The learner interacts with the larger natural, social, and technological (NST) aspects of the surroundings. As a result of these interactions, individuals figure out how their differences can work best for them in their NST surroundings.

Feedback loops are a strategic device that enables learners to turn their jagged individual profiles into a system of effective interactions with the NST surroundings. It allows them to critically reflect on their actions and take control of the next steps by adjusting them according to their evaluations of previous steps. And this becomes a strategy for designing an individual repertoire of knowledge and skills, which in turn leads to the development of individual agency and ultimately self-realization.

These three theoretical aspects—individual agency, systemic thinking, and feedback loops—now have to be examined in the context of cognitive structures or, as Piaget defined them, mental schemata.

In R@W, we adopt Piaget’s concept of cognitive development.

At the foundation of Piaget’s concept is the idea that a child’s knowledge acquisition is accompanied by the construction of his or her unique mental model of the world. It starts from the first breath the child takes and never stops throughout the life of the individual.

Let’s create a symbolic and greatly simplified map of this process.

So the child’s first breath, in an entirely unique natural, social and technological (NST) context, influenced by the child’s genetic predisposition, results in a certain physical and emotional snapshot.

Let’s call it a mental grasp.

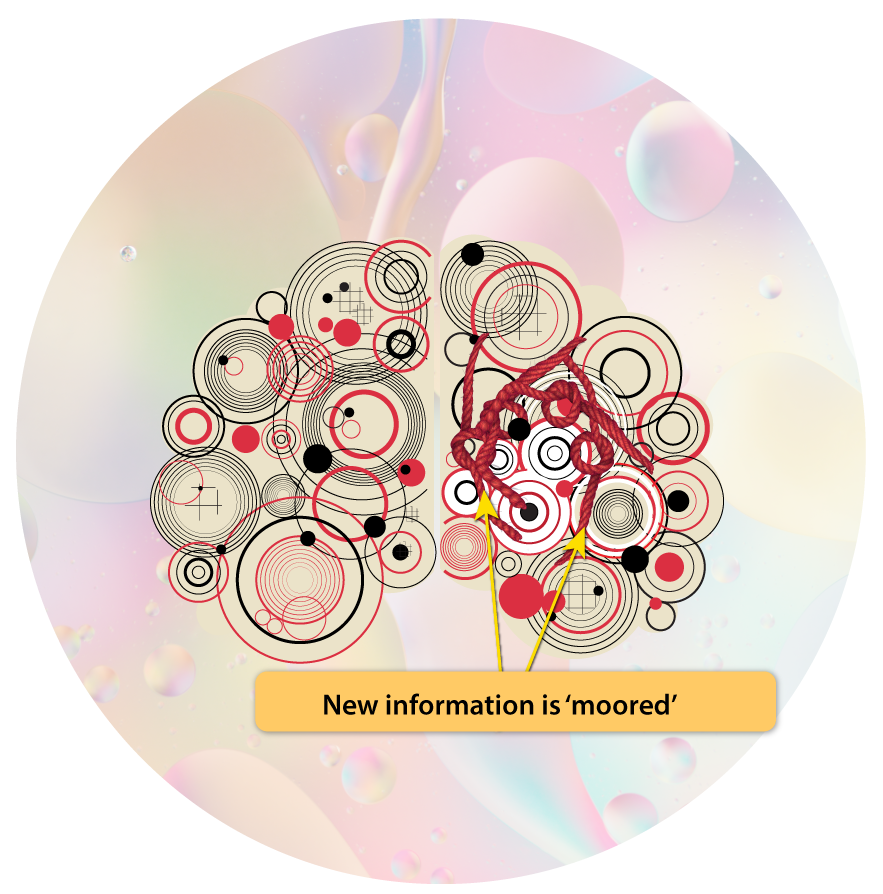

We will represent the various mental grasps of an individual as a unique composition of circles. Just as individuals have unique genetic predispositions and experiences, the different mental grasps are shaped by varying contexts, life circumstances, and emotions, which make them all unique. We use those mental grasps as building blocks to map out abstract mental schemata.

From Piaget’s Mental Schemata to the R@W Learning Concept

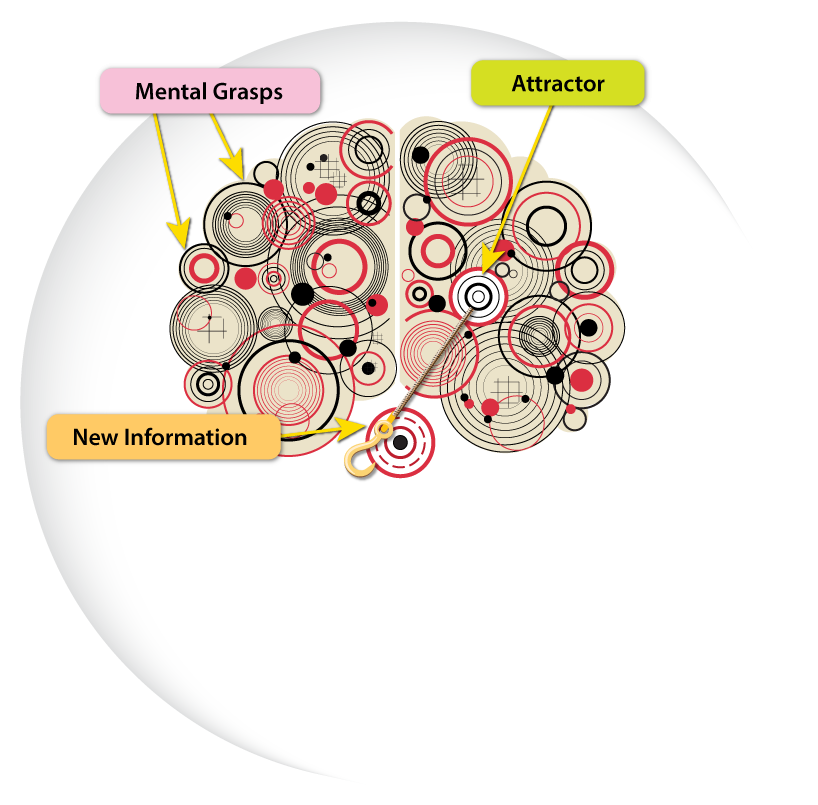

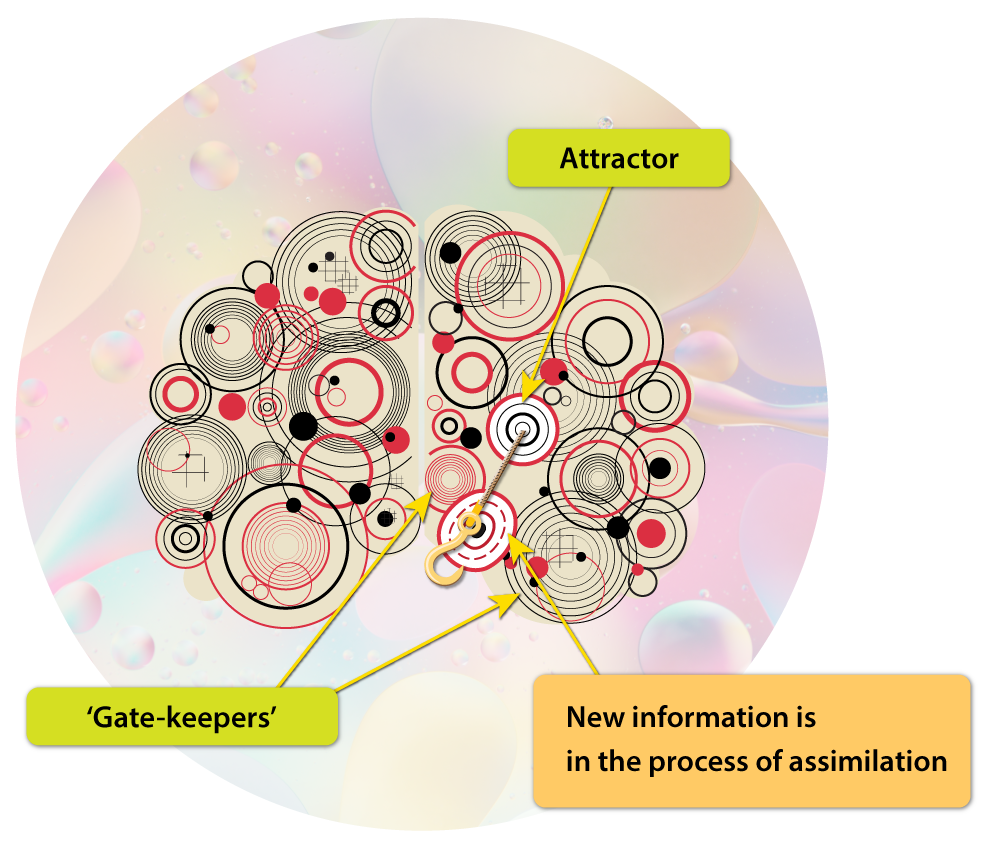

For a piece of new information to enter the mental schemata, it has to relate to elements within the pre-existing structures.

In other words, you can’t explain algebraic formulae to a three-year-old child. It is also impossible for the individual to understand or learn the information explained in an unfamiliar language.

The existing elements within the structure have to recognize and catch (or hook) something familiar in the new information in order to let it inside the structure.

In addition, the learner has to be motivated in some way to allow the new knowledge to get inside his or her mental schemata.

It can be an extrinsic motivation: passing a test to demonstrate understanding of the learned material, or getting an expected external reward. Or it can be an intrinsic motivation: the learner ‘lets in’ the new information because of his or her individual curiosity, interests, concerns, imagination, and special likings for certain activities, places, or tools. These individual attributes that trigger intrinsic motivation we will call ‘attractors’.

The learner is drawn to understand new material because of an attractor. It is like a key that unlocks a door to get inside the mind.

This step of cognitive development Piaget defined as assimilation.

Assimilation is not always a smooth process as the new information has to pass through established elements of knowledge within the cognitive structures that play the role of ‘gatekeepers’. They can be beliefs, attitudes, or doubts that may need to be somehow re-adjusted to accept new information

According to Piaget, the new information is assimilated by and also accommodated within the mental schemata. This means that the structures themselves have to be changed. It may be only a slight change, but it is a change nevertheless. In addition, the new information has to be modified in congruence with the existing structures.

If the information was assimilated as a result of extrinsic motivation, the goal of its accommodation is to stay within the mental structures only temporarily, until the reward is received. It can be compared with a business stay in a hotel. When the deal is done or the test is passed, the visitor checks out.

In R@W the emphasis is placed on individual preferences and traits, as they are considered to be the attractors anchoring new information and drawing it into mental structures.

These attractors of learning also become agents that facilitate the process of adjusting new information to existing cognitive structures and mooring it securely within them.

If the information has entered the mental schemata due to affinity with the attractor, through intrinsic motivation, the new information becomes an integral part of cognitive structures.The methodology of experimenting, reconstructing and re-adjusting the new knowledge, combining it with the existing knowledge, skills, materials and tools, Professor of Information Systems, Claudio Ciborra described as bricolage. This methodology of learning and innovation is discussed on a separate page on this website.

It involves reinventions, improvisation and serendipitous occurrences. Bricolage involves tinkering that helps the new information to get better accommodated—growing into cognitive structures.

In R@W we use the image of a knot and the action of mooring to describe this stage of cognitive adaptation. The information gets woven into the mental schemata.

REFERENCE

Piaget, J. (1950). The Psychology of Intelligence [Kindle version, 2003, p.8]. M. Piercy & D.E. Berlyne (trans). Routledge: Taylor and Francis e-Library.