Creativity as an Evolutionary Property

From my experience, creativity among educators is commonly understood in relation to creative disciplines—the arts. For example, a person who is a well-trained violin player may be referred to as ‘creative’.

Another common understanding of creativity is when an art product is defined as ‘different’, with an air of reverence attached to it, as if making or understanding such a thing is only granted to some very special people.

R@W’s understanding of creativity has no relation to either of these views.

Every human being is naturally equipped with creative potential by virtue of being part of the evolutionary process. As the hallmark of the evolution of life, according to the Austrian-American physicist Fritjof Capra, ‘creativity—the generation of new forms—is the key property of all living systems.’[1]

R@W creativity is ingrained in useful real-world creativity. As Gauntlett states in his 2011 book Making Is Connecting:

We don’t only say that something is ‘creative’ when it has been recognized with a Nobel prize, nor do we limit the label to the kind of thing that each of us only does once or twice in a lifetime. Because we are inventive human beings, creativity is something we do rather a lot and understood in this broad sense it includes everyday ideas we have about how to do things. [2]

Because we ‘do’ creativity ‘rather a lot’ in a wide array of our daily experiences and not with a specialized professional approach, the R@W pedagogy focuses on the type of creativity that is associated with do-it-yourself (DIY) practice. R@W DIY culture signifies learning through creating, where the outcome of the learning process is assessed not by the level of professional standard attained, but by the depth and scope of the knowledge acquired and the development of agentic strategies. R@W DIY creativity starts with individual interests and is charged with the willingness to take risks, to experiment, and to come up with unique and useful solutions for an identified problem.

Creativity as Novelty and Usefulness

Creativity is a concept characterized by novelty and usefulness.

Creativity is an autopoietic (self-designing) action. Like all other aspects of the R@W system, creativity emerges through ‘churning’ between ‘pushing at and pulling’—between being willing to take the risk by thinking outside the box (seeking improvement) and synchronizing it with what is already in the box (what is already working well). And by doing so an individual expands their own knowledge and extends the boundaries of existing knowledge. Creativity is driven by individual talents. But it receives recognition and acceptance when, in some brave new way, it manages to satisfy the existing needs of others.

DIY Creativity

R@W advocates a DIY approach to creativity. Excellent knowledge and skills in a given discipline without the attempt to find something novel are not the manifestations of creativity. At the same time, a lack of the knowledge and skills required to complete the task to a certain level may inhibit the usefulness of the result, which consequently wouldn’t be considered creative.

What this means is that knowledge of and skill in a discipline facilitate the production of novelty. But, at the same time, novelty is by definition something that has not been practiced before and therefore the ways of achieving it have yet to be found. To avoid being constrained by a lack of professionalism, the concept of a DIY approach comes in useful. Through trial and error, novelty refines itself and finds its way into professional practice.

R@W Creativity & Bricolage

R@W is creative learning. It uses the methodology of bricolage, described on the Bricolage page of this website. Bricolage, in R@W, is understood as learning by innovating, whether it is the innovation of concepts, products or organizations. The innovations are achieved by using what the learner knows, has the ability to do and, most importantly, has an interest in doing. The learner develops the skills of smart thinking when they find an effective way of solving problems by applying their personal knowledge, abilities and interests. The important technique in this process is strategic tinkering. The R@W learner follows his or her intuition and improvises without fear of failing. In R@W, the extent of their learning will be measured not by the finished product or concept, but by the extent of the novel material and the effectiveness with which it is incorporated into the learner’s existing knowledge in the course of the learning project.

R@W DIY Creative Strategies

The R@W model identifies three types of creativity and implements them as three stages of the individual creative learning process:

- combinational stage

- exploratory stage

- transformational stage.

Combinational creativity is a feast of combinational feats.

It is important to remember that at this stage, fluency, flexibility and originality are the guiding terms for generating curious juxtapositions and unexpected cross-fertilizations. A number of variations have to be considered and created before we move on to the next stage.

Combinational Stage—Curious Juxtaposition and Unexpected Cross-Fertilization

Combinational creativity stems from the principle that ‘an idea is nothing more nor less than a new combination of old elements.’ This stage of ideation usually coincides with a limited understanding of the topic at hand, without much knowledge having been gained yet. Because of this, learners haven’t managed to form definite opinions or beliefs on the subject and they are relatively free to engage in such ‘daring’ processes as ‘curious juxtapositions’ or ‘unusual cross-fertilization’.

Let’s define these two terms.

Curious juxtaposition—positioning two or more objects from different contexts of life in a way that creates a surprising and thought-provoking effect.

Unexpected cross-fertilization—blending the elements from different contexts of life into some meaningful concept or functional device.

This stage of ideation can be equated with what is commonly known as brainstorming. In groups, ideas are expressed and recorded in words, as many as possible. Working on their own, students use group-generated ideas as well as their own. This is a process of strategic tinkering. The students hand-draw rough sketches or stick figures, or use primary shapes to express their thoughts. In their multimodal journals, students utilize the affordances of the software at hand. They can roughly ‘cut out’ elements from images and photos found on the Internet, juxtapose and cross-fertilize them in various ways.

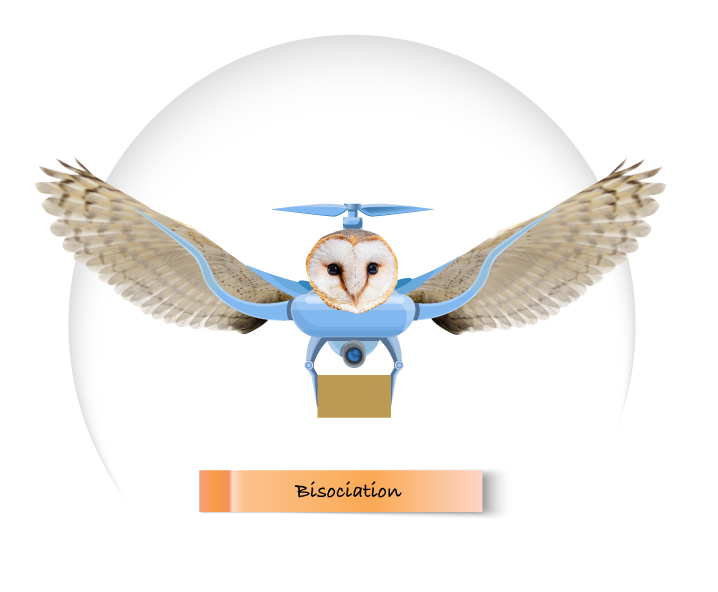

Exploratory Stage—Bisociation

Exploratory creativity follows the first wave of idea generation.

This is the time to notice and think about how the generated juxtapositions and cross-fertilizations are connected to a topic under the discussion. For instance, the two examples using a barn owl and a drone that I offer here suggest that the given topic concerns flying.

Now we can think more deeply about flying objects from two different contexts and their association with the problem that needs to be solved. The key term here is ‘bisociation’.

The term ‘bisociation’ was coined by Hungarian-British journalist and author Arthur Koestler in 1964 in his book, The Act of Creation.[4]

Bisociation—bi = two + association—is about identifying the similarity between objects or concepts from different domains of life that are in some way important to the topic at hand. Bisociation is therefore looking for a likeness between the objects and combining them on the basis of this likeness, which is often unexpected.

Let’s look at our combinational activities.

We only have space here to touch briefly on how the creative process unfolds. So we will zero in on the general topic—‘flying’—and how the examples from two domains of life (‘bi’) can be ‘associated’ with each other in a coherent and meaningful cross-fertilization.

In our examples of curious juxtaposition and unexpected cross-fertilization, we find unstable equilibrium and disturbed emotion and thought resulting from remixing an organic form—the owl—with a technical device—the drone.

Is this even possible?

If the drone is attached to the head of the owl, as in our curious juxtaposition example, wouldn’t it be rather disturbing to see the owl (even if it is man-made) being pulled up by its head?

And if the wings of the owl are attached to the drone’s body, how would they work together with the propellers? And why do we need the wings if the drone’s propellers enable it to fly?

These are the questions that take the learner from the combinational to the exploratory stage of creativity. To proceed with the exploration, the learner needs to know what is the intended purpose of the project, its target audience, context, constraints and limitations. Unless you establish the parameters, the exploration is likely to be unproductive.

The exploratory stage consists of strategic tinkering to establish the validity of the bisociations that have been generated.

This doesn’t mean that any further ‘feats of association’ should be declined. On the contrary: when more knowledge has been generated, more effective juxtapositions or cross-fertilizations may come into view and be more impressively incorporated into the project.

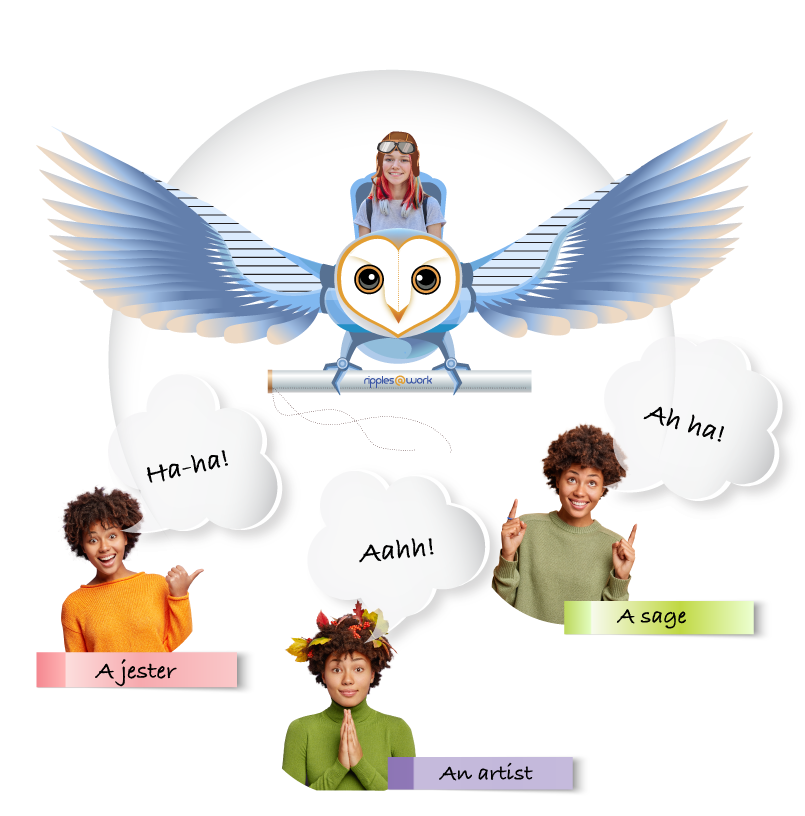

Transformational Stage—Jester, Sage, and Artist

The combinational stage of R@W learning by innovation is spontaneous, aimed at breaking through inhibitions.

The exploratory stage is more focused. It is when the ‘anything goes’ combinational approach is replaced with a focused exploration of the validity of the spontaneously generated ideas.

The transformational stage in R@W creative learning takes place when the strategic tinkering of the combinational and exploratory stages reaches a point of illumination.

The transformation that happens at this point is twofold. First, there is a change or conversion of the idea or product under consideration into a different principle or form. This is the aim of any professional creative process.

In R@W, on the other hand, we are more concerned with the second type of transformation, which is the expansion of the knowledge base and the improvement of the life-smart skills of the learner. It doesn’t matter if the product or concept is unworkable or incomplete, even though that would be unacceptable in real professional life. During their formative years young people should be able to afford to focus on their production of selves. But this opportunity is taken away from them by formal schooling.

In R@W, however, the transformation of the learner and their self-design of a repertoire of personal life-smart strategic techniques is the gist of the learning process.

If the learner can explain how he or she learned what they learned and they know how to apply their knowledge in real life from the examples of their learning project, then it is their ‘Eureka!’ or lightbulb moment.

Transformational creativity in R@W correlates with Koestler’s triad of roles: Jester, Sage, and Artist.

The Jester plays with absurdities, taking them to pieces and rearranging them in unthinkable ways, producing ludicrous results and making people laugh. The Jester’s creativity can manifest in a ‘Ha-ha!’ moment.

The Sage pays attention to facts and functions. The Sage points at new relations between observed things and tries to explain them. The Sage’s creative achievement is revealed in an ‘Ah ha!’ moment.

The Artist recombines, making things fit with each other in a new way, inducing feelings of appreciation, empathy, and other emotions, sometimes unexplainable but clearly perceivable. The Artist’s creative achievement is the “Aahh!” moment.

The Ha-ha!, Ah-ha! and Aahh! moments are the yardsticks for the learners to know they are achieving creative transformative results. The presence of these moments is also the yardstick for an assessor to gauge the creative process, which is usually a very difficult endeavor.

The final outcome is when the group project comes to a conclusion—whether it is a concept, a new organization of things, or a product—where the daring wittiness of the Jester, the rationality of the Sage, and the aesthetic appeal of the Artist come together in one harmonious amalgam.

Creative Learning Ripplework

I didn’t set up a particular goal for the hypothetical example of the creative process I presented here, so we can’t discuss its specifics.

But we can say that the context of learning that we have here can be described as a ripplework—a dynamic churning of the following ripples-aspects:

- the daring of the Jester in cross-fertilizing two incompatible things by declaring ‘Why not?’;

- the rationality of the Sage in asking ‘Why’ and ‘How’;

- the striving of the Artist to answer the question, ‘How can we make the experience pleasing?’.

The learning ripplework of asking Jester, Sage, and Artist questions, generating data and ideas in response to them, analyzing and experimenting with them and so on, may lead to learning such topics as:

- forces of flight: weight and lift, thrust and drag;

- why planes, helicopters and drones need propellers to fly and birds don’t;

- how birds’ wings and muscles work to facilitate flight;

- the possibility of a flying machine based on wing movements;

- the possibility of generating wing movements by human pedaling.

To know more about Jester, Sage and Artist techniques and the assessment of creative learning, enroll in the R@W_Pedagogy course.

REFERENCES

- Capra, Fritjof (n.d.). AZQuotes [Website]. Retrieved, 4 January 2018, from: AZQuotes.com. http://www.azquotes.com/author/17669-Fritjof_Capra

- Gauntlett, David (2011). Making is Connecting [Kindle version]. Polity Press. Retrieved from: Amazon.com

- Boden, Margaret (2013). Creativity as a Neuroscientific Mystery. In O. Vartanian, A. S. Bristol & J. C. Kaufman (Eds). Neuroscience of Creativity (Kindle version). Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Koestler, Arthur (1964). The Act of Creation [p. 36]. London: Arkana, The Penguin Publishing Group