The Elements of Cinematic Writing

Multimodal writing is when you write using text, images, sounds, and animations.

When starting a Ripples@Work learning project and collecting data to become familiar with the topic, you use multimodal writing. At R@W, multimodal writing is also used to organize and analyze data, reflect on thinking and behavior, and represent mind processes, which are called mind-cinema. It is similar to thinking out loud but with the use of text, images, sounds, and animations.

Multimodal writing is not only about presenting facts and showcasing new knowledge. It is about analyzing and taking control of your thinking. As you become more self-aware, you can discover ways to optimize your positive traits and develop your unique ways of communicating. In other words, you are developing skills to act upon the best individual traits to achieve a set goal that is recognized as an individual agency. And that is what we aim for at R@W.

By doing this, you engage in metacognitive activities, which means thinking about your own thinking. At R@W, we take it a step further by using technology to represent personal experiences through multimodal forms, and we consider this approach as cinematic writing.

Cinematic writers have an array of multimodal tools at their disposal.

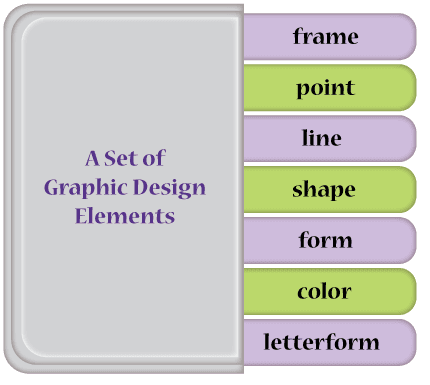

In this document, you will become acquainted with the first two sets: GD elements and media generated assets, and complete some exercises. The R@W way of learning involves interacting with the tools and materials at hand. Therefore, in the next document, I will provide an overview of cinematic writing and give an example of starting a learning project.

A set of graphic design (GD) elements that can be used in PowerPoint (PP). R@W recommends using this user-friendly, universal, and sufficient software. Additionally, working in a group is more efficient when everyone is on the same platform.

A package of generated data—including media assets.

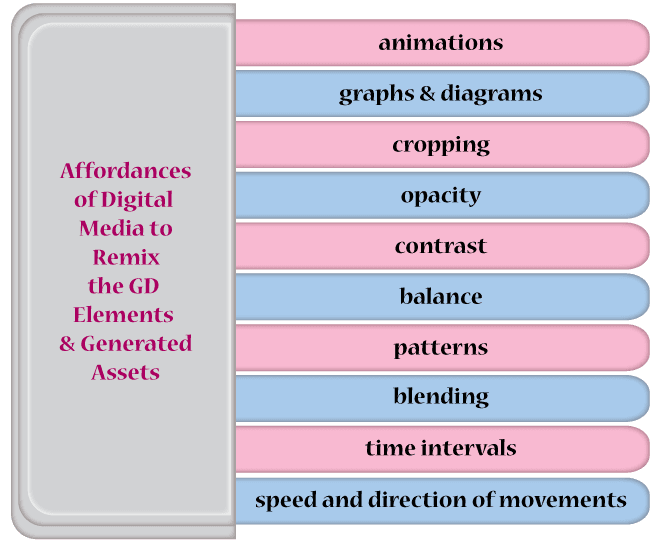

A repertoire of digital affordances that allow for the creation of multimodal remixes using various elements and assets.

Graphic Design Elements

The element of graphic design, to begin with, is space. The cinematic writing page is defined by the boundaries of the page, which we refer to as a frame.

Cinematic writing elements are always experienced in relation to a frame. The figure-ground relationship is created when an object is placed within the space of a frame. This is the first step in your cinematic writing adventure.

Sample

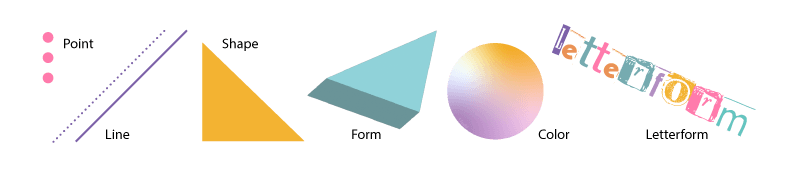

The next design element to consider is the point.

With a point, we can create texture, strokes, patterns, and points of connection.

You can also refer to the point as the dot.

Sample

The next element to look at is the line. It can be used to emphasize, connect, create texture or patterns, point to or lead to particular areas of the frame with arrows, represent intersections, be used in diagrams, and create wireframes or tangles.

Exercise

Let’s do some exercises with the line that will also involve using points.

Open a new page frame in your cinematic journal (CJ).

To draw a line in PP, use the Shape tab. Choose the line tool and draw a line on the page.

Select the drawn line, press the Alt (Windows) or Option (Mac) key, and drag the line down to duplicate it. Repeat this operation a few times to have a few lines.

On the right side of the toolbar, click the Format pane. In this area, find tools to experiment with the drawn lines by applying different effects to the lines, such as color, thickness, and other qualities.

Go back to the Shape tab, select the Oval shape and draw two points/dots on different sides of the page.

Now draw a line with arrows at its ends to point at the dots and experiment with different types of arrow-ends by selecting them from the Format pane.

Example

Exercise

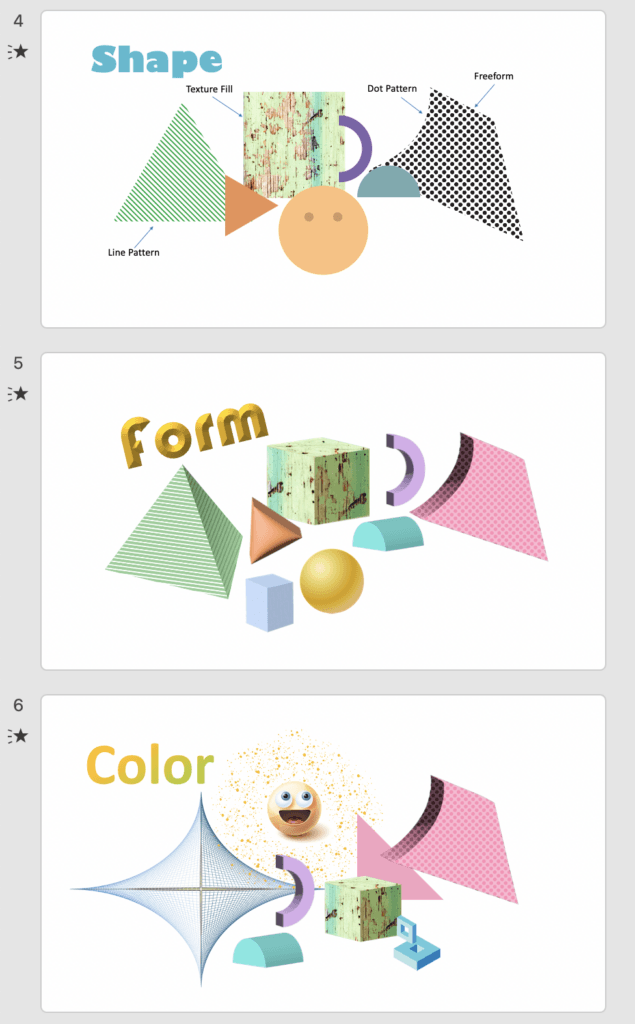

The shape is an element that exists within an area outlined by a line or filled with color, pattern, or texture. In other words, shapes are always created with the use of other elements.

We can create a shape by selecting a geometric shape from the Shape tab or drawing a shape free-hand. Draw a few different shapes and apply various qualities to them using the Format pane.

Note that the Shape tab may move from the right to the left side of the PP interface to better see the area you are working on.

Experiment with different types of fills. You can use solid or gradient fills and experiment with different colors.

When you apply patterns, the shape is filled with points/dots or lines arranged in a repeated geometric order. When you use texture, you apply a computer-generated simulation of the feel of the surface, such as wood, canvas, or marble.

Example

Exercise

In Ripples@Work, we differentiate between shape and form. We refer to shapes as areas defined by contour, color, pattern, or texture. Shapes are two-dimensional figures that have either width and length, or height and length, or height and width.

We consider a figure that has an added third dimension, depth, as a form – a 3-D object. The third dimension can be applied either by the addition of a third geometric facet or created by the illusion of shadow and light.

To choose the form, select it from the Shape tab. Alternatively, you can insert 3-D objects from a file.

Example

Exercise

An essential design element is color. And in experimenting with points, lines, shapes, and forms, we have already experimented with color. The color element carries an abundance of emotional meaning, conveying messages on a subliminal—or visceral (feeling rather than understanding)—level of perception. Color can be used for emphasis, contrast, separation of elements, and color-coding. Cinematic writers can engage more deeply with their inner world of experience by using color to create a specific atmosphere when working with multimodal representations.

Example

Exercise

The last tool in our graphic design set is the letterform. In R@W, type can be used as an image. It is as important as any other element in cinematic writing. Type can be used as separate letters, acronyms, or words, and can become a dynamic part of the overall choreography of the cinematic message. The text can also be used as annotations that the cinematic writer works with to weave together the event’s elements.

As with other graphic design elements in cinematic writing, the use of the letterform is enhanced by the capabilities of digital software. In this visual example, I typed each letter of the word “letterform” separately and applied WordArt effects from the Insert bar.

Since “letterform” is a long word, use your name to experiment with different WordArt options. Shorten your name if necessary to only four or five letters.

Choose the effect you prefer and type one letter at a time. Then repeat the process with the other letters. I recommend typing each letter separately so that you can move them individually and arrange them into the desired composition.

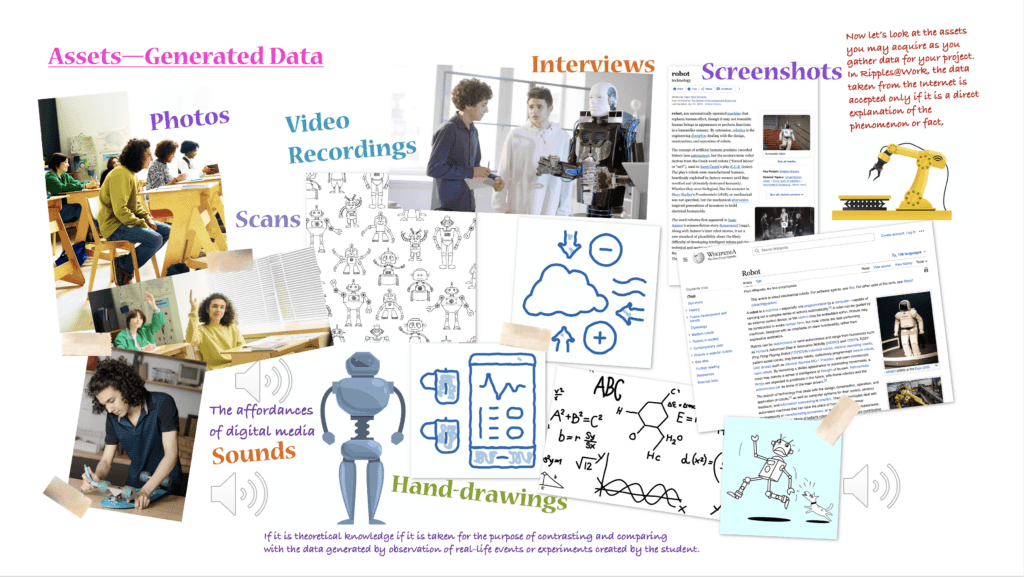

Media Assets

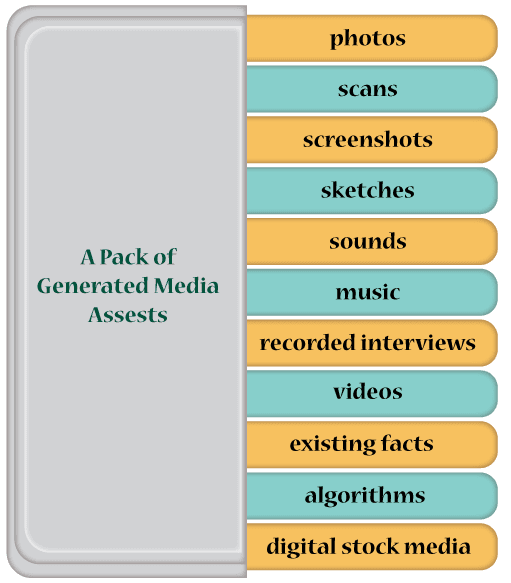

Let’s explore the media assets you acquire as you gather data for your project. In Ripples@Work, data taken from the internet is only accepted if it complements the data generated by observations of real-life events or experiments created by the learner. Learners develop their data by interacting with the surrounding world and employing existing online resources to analyze and galvanize their collected material.

Regarding my use of online digital assets, I use an EnvatoElements subscription to obtain video clips, sounds, photos, and much more. It is acceptable to use some media ‘hooks’ to initiate a project and get yourself in the mood. However, as you progress, you need to develop your own media assets because they will be evidence of your own observations and experimentations.

Here, I have organized the ‘raw material’ – the assets you can use for the production of your knowledge – into categories: photos, video recordings of interviews, audio recordings and sounds, screenshots, and hand drawings.

Cinematic writing is a meaning-making process of creating significance or purpose in one’s life experiences. It involves taking information from the environment and using it to construct personal meaning. This process is essential for individuals to make sense of their lives and create a sense of coherence. In making meaning with cinematic writing you can develop your own way of allowing the “bits” from the inner world of your mind-cinema to be materialized and embodied in a perceivable form. In doing so, you are using the elements of graphic design, enhanced by digital technology, and the data you have generated (and continue to generate) for the project – assets. Some of the gathered elements of data can be physical objects, such as an old shoe. To use them for cinematic writing, you turn them into digital assets by taking digital photographs or scanning them.

The affordances of digital media are used to remix graphic design elements with generated assets and existing knowledge.

The next document will look at the affordances digital technology provides us for remixing available graphic design elements, generated assets, and existing knowledge in individually unique ways that help us make meaning of the resulting patterns. That is to say, you explore a given topic from the perspective of your interest in order to understand and explain things that you did not know before starting the project.

For a cinematic writing example, please refer to the Cinematic Writing Example document.